Section: New Results

Fundamentals of Interaction

Participants : Sarah Fdili Alaoui, Michel Beaudouin-Lafon, Cédric Fleury, Wendy Mackay, Theophanis Tsandilas.

In order to better understand fundamental aspects of interaction, ExSitu studies interaction in extreme situations. We conduct in-depth observational studies and controlled experiments which contribute to theories and frameworks that unify our findings and help us generate new, advanced interaction techniques.

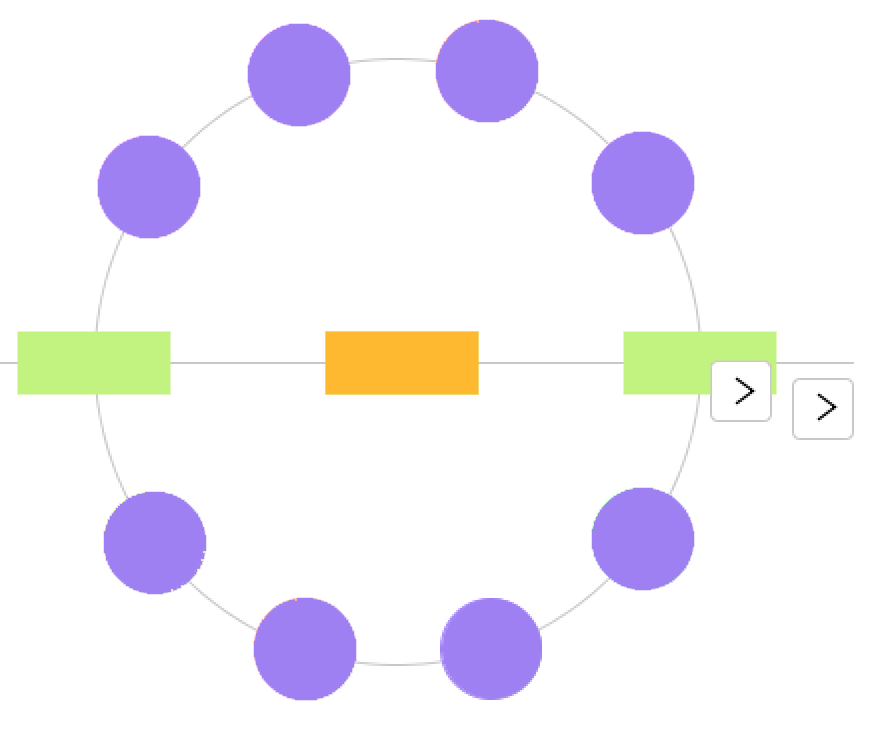

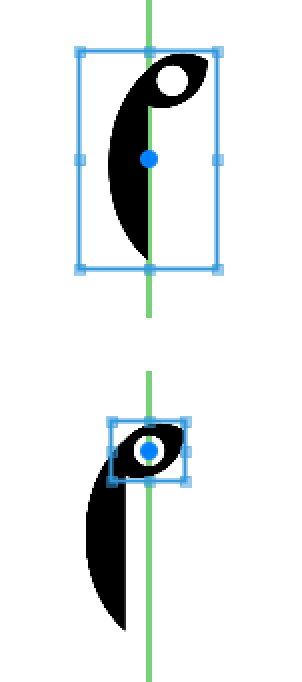

StickyLines – Aligning and distributing graphical objects is a common, but cumbersome task. We studied graphic designers and regular users and identified three key problems with current tools: lack of persistence, unpredictability of the results, and inability to ‘tweak’ the layout. We created StickyLines [14], a tool that reifies guidelines into first-class objects: Users can create precise, predictable and persistent interactive alignment and distribution relationships, and can ‘tweak’ the alignment in a way that can be maintained for subsequent interactions (Figure 2). We ran a [2x2] within-participant experiment to compare StickyLines with standard commands and found that StickyLines performed up to 40% faster and required up to 50% fewer actions than traditional alignment and distribution commands for complex layouts. Finally, we gave StickyLines to six professional designers and found that not only did they quickly adopt it, they also identified novel uses, including creating complex compound guidelines and using them for both spatial and semantic grouping. This work demonstrate the power of reifying concepts, such as alignment and distribution, into first-class objects that can be directly manipulated and appropriated by end users.

|

UIST Video Browser – We created an interactive video browser that provides a rapid overview of the 30-second video previews of the ACM UIST conference papers, based on the conference schedule [16]. The web application was made available to the 600+ conference attendees, who could see an overview of upcoming talks, search by topic, and create personalized, shareable video playlists that capture the most interesting or relevant papers. Reifying playlists into first-class objects and applying instrumental interaction concepts helped create a fluid and efficient interface.

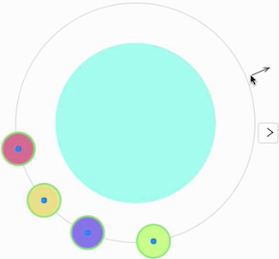

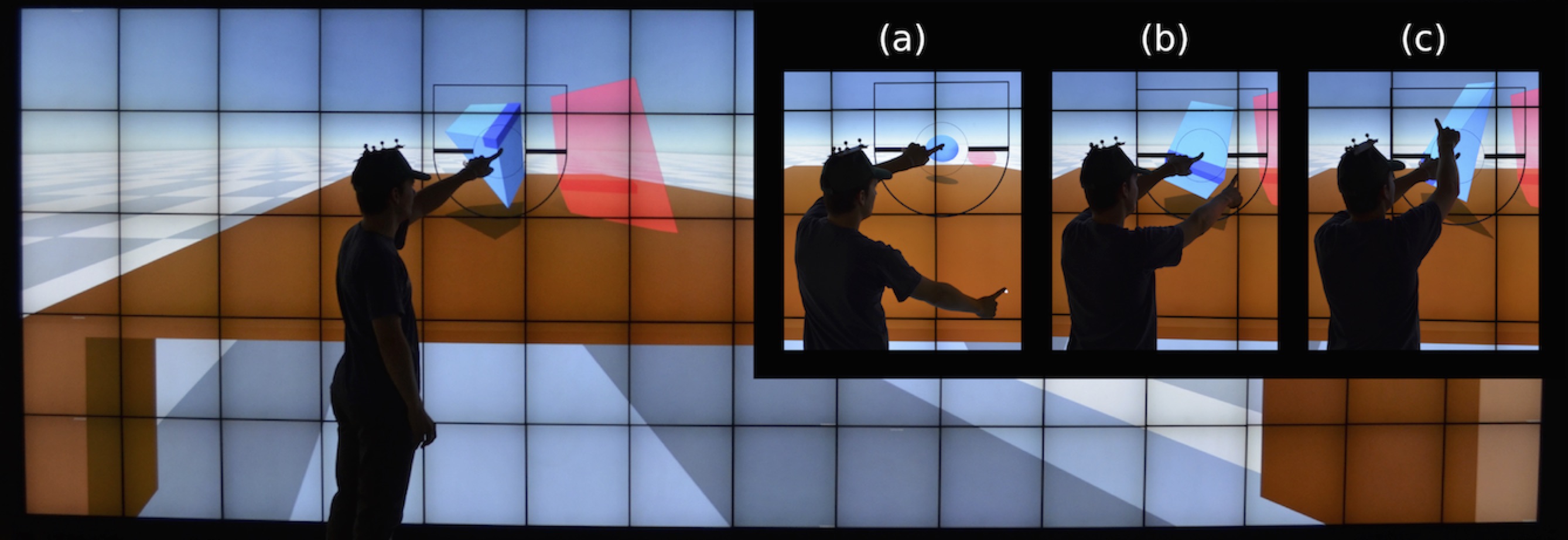

In(SITE) – We explored touch-based 3D interaction in the situation where users are immersed in a 3D virtual environment and move in front of a large multi-touch wall-sized display. We designed In(SITE) [20], a bimanual touch-based technique combined with object teleportation features which enables users to perform 3D object manipulation on a large vertical display (Figure 3). This technique was compared with a standard 3D interaction technique. The results showed that participants can reach the same level of performance for completion time and a better precision for fine adjustments with the In(SITE) technique. They also revealed that combining object teleportation with both techniques improves translation tasks in terms of ease of use, fatigue, and user preference.

|

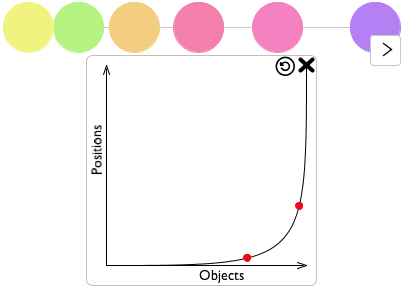

In collaboration with Inria Lille (MJOLNER group) and Univ. Strasbourg, we applied our design principles for instrumental interaction to create new interactive tools for the parallelization of programs, a highly specialized task that is currently done by expert developers. Current programming models, languages and tools do not help developers restructure existing programs for more effective execution. At the same time, automatic approaches are overly conservative and imprecise to achieve sufficient performance. We introduced interactive program restructuring [28], [11] to bridge the gap between semi-automatic program manipulation and software visualization. First, we extended a state-of-the-art polyhedral model for program representation so that it supports high-level program manipulation. Based on this model, we designed and evaluated a direct manipulation visual interface for program restructuring. This interface provides information about the program that was not immediately accessible in the code and allows to manipulate programs without rewriting code. By providing a visual and textual representation of an automatically computed program optimization that is easily modifiable and reusable by the developer, we create a sort of human-machine partnership where the developer can better take advantage of the power of the machine. An empirical study of developers using this tool showed the value of program manipulation tools based on the instrumental interaction paradigm. This work illustrates how the combination of our conceptual approaches, namely instrumental interaction and human-computer partnership, can benefit extreme users such as developers of parallel programs.

Finally, we reviewed statistical methods for the analysis of user-elicited gestural vocabularies [24]. We showed that measures currently used to assess agreement between participants of a gesture elicitation study are problematic. We discussed the problem of chance agreement and showed how it can bias results. We reviewed chance-corrected agreement coefficients that are routinely used in inter-reliability studies and showed how to apply them to gesture elicitation studies. We also discussed how to compute interval estimates for these coefficients and how to use them for statistical inference.